A Brief History of Kersal Page 2

|

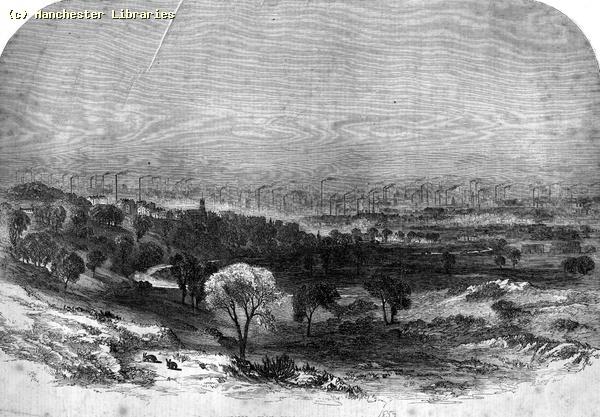

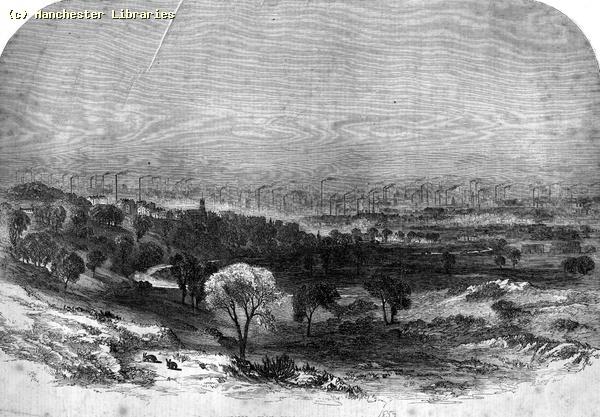

A picture of Kersal Moor, 1857. |

Kersal Moor And Chartism The Anti-Corn Law League Due to fierce competition from cheap imported foreign corn in the early 19th century, wealthy and influential gentlemen farmers had lobbied the ruling parliamentary party, the Tories, to prohibit their import by the imposition of Corn Laws in 1815. With this monopoly in place, British corn rose to prohibitive prices, making it impossible for the poor to buy bread. The Corn Laws were seen by ordinary people as a symbol of the dominant ruling aristocracy's feudal power over them, and of the suppliers' unashamed self interest, at the cost of their staple food. Protests by Lancashire mill-workers at the imposition of such severe measures soon grew. In September 1838, mill owners and local politicians joined protesters in the formation of an Anti-Corn Law League, at the York Hotel in King Street, Manchester, with George Wilson as its chairman. Support grew so fast that a temporary wooden hall was built in St Peters Street to hold protest meetings - it became known as the Free Trade Hall. Later a stone building replaced this original wooden one. Two major figures emerged as leaders of the Anti-Corn Law movement,Richard Cobden, a Bolton calico manufacturer, and John Bright, a Rochdale mill-owner and a Quaker. Cobden and Bright, both persuasive orators with powerful local backing, (including Archibald Prentice radical editor of the Manchester Times newspaper), succeeded in getting elected to parliament, (Cobden - MP for Stockport in 1841) where they constantly lobbied and harassed the Prime Minister, Sir Robert Peel (born in Bury). Peel, under severe pressure from the League and its growing band of ever more powerful supporters, repealed the Corn Laws in 1846, thereby splitting the Tory party, and effectively ending his own political career in the process. Manchester would, henceforth be associated with the principle of Free Trade. The Free Trade Hall, the third and now a fine permanent stone building, was built later as a monument to honour the Manchester movement. The Reform Movement- Radicals And Chartists By the early 19th century, despite its massive growth, Manchester had no real political representation - most parliamentary places were held by local gentry in surrounding suburbs, who had little or no political interest. Many of these 'constituencies' comprised no more than a half dozen houses. The vast majority of Manchester people had no voice, and were not represented in parliament. Many educated businessmen of the region thought it high time that the political system should be reformed so as to be more representative of the contemporary demography - most constituencies and boundaries had been drawn over 400 years earlier, and bore little resemblance to actual population distribution at the time. The Reform Movement had begun as early as 1790, when the Manchester Constitutional Society had been formed, under the leadership of Thomas Walker. This "radical" movement was deeply suspected and opposed by local churchmen and magistrates, largely conservative in their attitudes, and in privileged positions, who were generally satisfied with the way things were. The Peterloo Massacre A public reform meeting was called, to be held on Monday 16th August 1819 in St Peters Fields (now St Peters Street), as there was no building thought big enough to hold the anticipated crowd. Henry Hunt , a national reform leader, and noted orator who had spoken elsewhere that year, was to address the crowd. Estimates put the crowd at variously 30,000 and 150,000 people - in any case, we can be certain that there were more people present than Manchester had ever seen in one place before. Disturbed such large crowds, magistrates called in local militia to stand ready. Some 1500 troops assembled, comprising the 15th Hussars (professional soldiers) and soldiers of the Manchester and Cheshire Yeomen Cavalry (a largely volunteer force), commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel Guy L'Estrange. Magistrates, fearing insurrection and riots, ordered Hunt and other leaders to be arrested before they could speak, though the meeting had been thus-far peaceful and orderly. Inadvertently a mounted solder brushed and knocked down a mother, killing the child she was carrying, and panic ensued. Magistrates, and the troop commander, misread what appeared to be a riotous outbreak, and ordered Yeomanry, who were standing ready just off Portland Street, to go in to break up the affray. The armed cavalry, sabres drawn, charged the crowd, cutting people down indiscriminately. Men, women and children were hacked down or trampled by horses or people in flight. After ten minutes of havoc and slaughter, the field was deserted except for the broken hustings platform, bodies of the dead, wounded and dying. A soldier of the Yeomanry company, who had fought at Waterloo in 1815, likened the carnage to that battlefield, and the term "Peterloo" took hold, and survives as an historic event even today. After news of the massacre spread across Britain, local authorities clamped down on all public meetings, in breech of all laws to the contrary, and took severe measures to ensure public order. It had been arguably the most important day in Manchester's political history. Rumours spread that the attack had been planned and may possibly have been ordered, well in advance of the event, by the government in London. Fears of the recent French Revolution permeated British political awareness to such an extent, that the authorities were paranoiac in case ordinary people followed the French example - local authorities had been ordered to stamp out any risk at source and summarily. Another viewpoint blames bystanders throwing stones provocatively at the troops. Debates on the causes of the Massacre continue. Meanwhile, Hunt and the other Peterloo leaders had been incarcerated in Lancaster Castle prison. Thousands of supporters lined the streets when, after being released on bail, Hunt made the return trip to Manchester. Hunt had always insisted on peaceful and legal means to achieve political change, despite being urged to armed protest by many of his supporters. The Peterloo Massacre successfully stifled Manchester's bid for reform for a decade. Stinging from the attack for many years to come, political meetings henceforth moved into the surrounding towns of Oldham, Stockport and Blackburn, where the predominance of mill-workers saw many eager to join the movement, and though somewhat muted for a time, the movement gradually grew - most popular amongst the unfranchised working people of Northern England. It was not to be until the 1830s and '40s that parliamentary reform could be fully ressurrected in Manchester. The Chartist Movement, begun in London, but taken up eagerly and pioneered in Manchester, was also a growing force. Chartists wanted universal suffrage for all men, secret ballots and annual elections. Political reform was in the air and the people of Manchester and the numerous spinning and weaving towns surrounding it, were at the vanguard of the movement. A Chartist meeting was held at Kersal Moor in September 1838, despite the Peterloo Massacre, and a second at the same site in May 1839. Another was held at the Griffin Inn in Great Ancoats Street in July 1840, and 6 other meetings in Lancashire in 1841. The Chartist Movement dominated British politics in the 1840s, and Manchester had been the flashpoint for the chain reaction which it caused, and for the eventual political reforms which were brought about through the constant efforts of its supporters.

From Victorian Manchester

At last, the party's roots are showing 'Our strength is in our union; our power is in our voice; and our success in our perseverance,' announced Chartist leader Fergus O'Connor to a rally of 30,000 on Kersal Moor in 1838, just one of a series of protests that were turning Manchester into Britain's premier socialist city. So, after decades at seaside resorts, it is right that the Labour party has returned to its radical roots with a conference at the heart of 'Cottonopolis'. And for a wobbly leadership, this city of rebels and revolutionaries could provide just the setting. August 1819 first earned Manchester its top spot in Britain's radical geography. The massacre of activists demanding the vote on the fields that came to be known as Peterloo (now the site of the G-MEX, venue for the conference) focused attention on the terrifying poverty and politics of the city. Unprecedented rates of industrialisation, along with a witches' brew of Protestant dissent, class divisions and Mancunian bolshieness, was hurtling the 'greatest mere village in England' into the forefront of socialism. That was why in 1842 a radical cotton merchant from the Rhineland turned up. 'The modern art of manufacture has reached its perfection in Manchester... and the manufacturing proletariat presents itself in its fullest classic perfection,' the young Friedrich Engels wrote. Arriving in the aftermath of the Plug Riots, when strikers pulled plugs from factory boilers, he was convinced the city stood on the verge of revolution: 'I forsook the company and the dinner parties, the port wine and champagne of the middle classes.' Instead, Karl Marx's collaborator took to the underworld of Chartists, Irish navvies and factory labourers. All in the hope of spotting the early signs of class war. Engels's account of Manchester's working world - its mills, wage slavery, rapacious machinery - provided material for Das Kapital. At Chetham's library you can sit at the table where Marx and Engels thrashed out the ideology behind the Communist Manifesto. Given this class-conscious politics, it was no surprise that the city inspired the founding of the Trades Union Congress. In 1868, the Manchester and Salford Trades Council gathered trade unionists from across Britain to press for political and legal rights. The birth of the TUC would give rise to the Labour party itself. The roots of British feminism can also be found in Manchester. Along Nelson Street, Emmeline Pankhurst established her Women's Social and Political Union in 1903 and, with it, the march to female suffrage. Yet there is another Manchester at odds with this pure Labour lineage. In Salford, powerful breweries and anti-Irish prejudice ensured a rock-solid Tory vote. But far more influential was liberalism. This was the city which gave voice to 'the Manchester School' - the free-market, less government liberals who did so much to define Victorian politics. Its heroes were Richard Cobden and John Bright, men who believed in the unalloyed power of commerce to deliver progress. Their acolytes transformed Manchester into what AJP Taylor described as 'the last and greatest of the Hanseatic towns - a civilisation created by traders without assistance from monarchs or territorial aristocracy'. Their monuments dot the city: the warehouses modelled on Renaissance palaces, the Athenaeum and Mechanics' Institute now united as the Manchester Art Gallery, and the romantic town hall, with its iconography of trade and industry. Their finest building reflects their finest hour: the Free Trade Hall was built to commemorate the repeal of the Corn Laws. It was, as Taylor put it, 'dedicated, like theUSA, to a proposition... the men of Manchester had brought down the nobility and gentry of England in a bloodless, but decisive Crecy'. From the Observer 24/9/2006 |

|

Nudism and Kersal Moor Walter Greenwood was born in Salford, Lancashire in 1903. He came from a poor working class family and left the local council school in Langworthy Road at the age of 13. Greenwood did a succession of poorly paid jobs but continued to educate himself by visiting the Salford Public Library. While out of work he wrote Love on the Dole (1933). This novel of life in a northern town during the depression was a great commercial success. He died in 1974 but seven years earlier he wrote his autobiography entitld There was a Time. In the latter he warites that young men used to have naked races on Kersal Moor. They said it was copying ancient Greek athletes, Greenwood's dad told him it was "so the lasses can way up form". This practice seems to have been indulged in by Roger Aytoun who acquired Hough Hall through marriage. It is said he was a Hero in the Siege of Gibralter. It is written that Roger first caught the eye of Barbara Minshull (elderly widow of Thomas Minshull a wealthy Apothecary and owner of Chorlton Hall and Garret Hall amongst others, all of which he left to Barbara) by winning a foot race on Kersal Moor in a "nude" State. They were married at the Colligiate Church (Manchester Cathedral)in February 1769, Barbara was then aged 65yrs. it is said that Roger was so drunk, he had to be held up throughout the ceremony. It appears that Roger then moved into Hough Hall and proceeded to squander his wife`s fortune. Barbara died 14yrs later. Roger by this time had to sell of most of his property to pay his debts, including Hough Hall. The amorous connection with the moor seems to have survived well into the 20th Century. Freda Lear writing on A Broughton Childhood( in Lifetimes Link, The Magazine of Salford Heritage in 2003) stated "Auntie Janet's bark was worse than her bite and she had the most wonderful sayings like "if you do that again I'll make you wish your father had never taken your mother on Kersal Moor." It took me years to understand what she meant."

|

|

Horse Racing

|

|

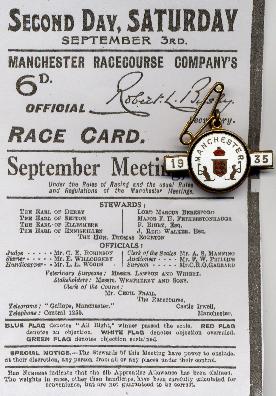

The Manchester races were held on Kersal Moor from 1730 till 1847, with a short interruption. 'A strange, unheard of race' for women in 1681 is noticed by Oliver Heywood as a sign of the times; From: A History of the County of Lancaster: Volume 4 (1911) |

|

While the modern racecourse developed largely in the 19th century, there are records of horseracing in Manchester from 200 years earlier, at Barlow Moor and Kersal Moor. The poet and writer John Byrom (who wrote Christians Awake) led an anti-racing lobby that kept the sport out of Manchester for 15 years, but it returned to Kersal Moor in 1760 and stayed there for nearly 90 years. In 1847 the Manchester Racecourse Company opened a course at Castle Irwell near the River Irwell, but after 20 years the ground was inherited by a man violently opposed to horseracing and gambling, who threatened to close them down. So the company bought 100 acres of land at New Barns two miles away, with two mile of the old ourse and gradually started to make a profit. In 1888 they introduced the Lancashire Plate with £10,000 prize money, then the most valuable race in the country. In the same year Buffalo Bill staged his famous Wild West

Show at the New Barns course. One event matched English thoroughbreds with American broncos over 10 miles and several changes of horse. The broncos won but only by 300 yards. Ten years later the company bought its former venue at Castle Irwell, while the New Barns site was acquired by the Manchester Ship Canal Company and incorporated into a dock extension. After four years of reconstruction the first meeting was held at Castle Irwell in March 1902 and in time it became one of Britain's leading racecourses, scene of exciting races by many champion jockeys such as Gordon Richards and Steve Donoghue.

In 1941 the Manchester

course held its first classic

the new St Leger Stakes

was run on 6 September,

watched by 56,000 spectators.

But horseracing in Manchester

finally came to an end on From the Manchester Forum |

|

|

LAST MEETING 9th November 1963 Geoff writes the following personal memories of a course he quite clearly, dearly loved and misses very much:- “I started going to Manchester Races in 1961; on my first visit Doug Smith rode a five-timer. I went to every meeting from that day to the last day's racing in November 1963. That day the famous Prince Monolulu was chanting 'I've gotta hoss'. Maybe it was one of Lester Piggott’s who needed five winners to overhaul Scobie Breasley for the jockey's championship. Unfortunately he only managed three winners, the last one being Fury Royal in the day's final race. The racecourse matched any course in the country in my opinion, and I’ve seen a few; not dissimilar to Haydock Park only Haydock is left handed and Manchester was right handed, I see they are thinking of building a new course, they should never have closed the old one as it was one of the best tracks in the country. Sadly missed by me and many hundreds of others” From http://www.greyhoundderby.com/Manchester%201935.htm |

|