A Brief History of Kersal Page 3

|

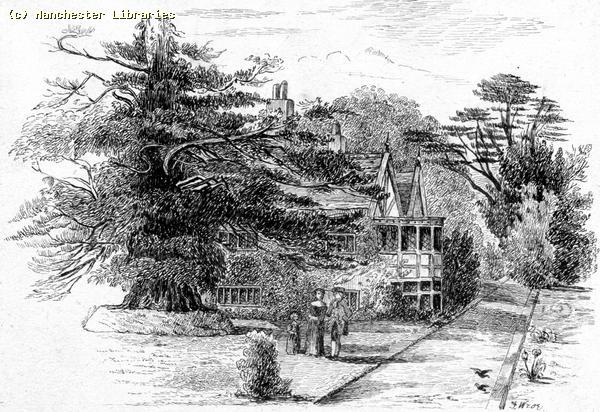

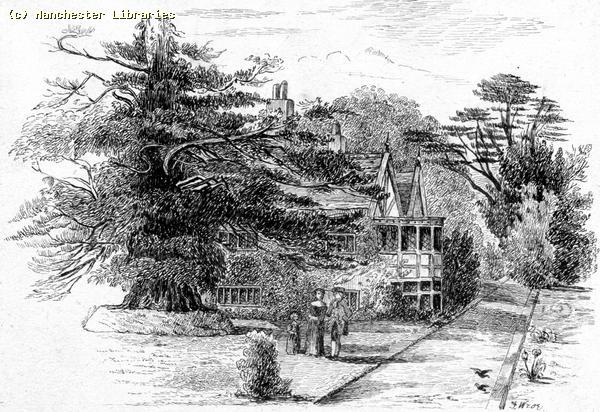

A picture of Kersal Cell.

|

On Floods

From Exploring Greater Manchester- a fieldwork guide, Web edition edited by Paul Hindle (Manchester Geographical Society). For more on flooding risks etc see here

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

On Golf

The quest for novelty was greatly encouraged by the newspapers which, costing three of four pence because of the tax, enjoyed a limite dbut influential circulation. "The true old English game of Cricket", pronounced the Whitehall Evening Post in 1767, "is now going out doors, and in the room thereof is instituted the Scotch game called Goff which is played practically everyday upon Blakheath." Prophesying such swings of fortune were meat and drink to journalists (often in more ways than one). Cricket was in no more danger the from golf than it was in September 1793 when the Sporting Magazine announced "Field Tennis threatens ere long to bowl out cricket" on the grounds that one patron had taken up the new vogue and another had dropped the old one. As for golf, the Blackheath and a similar group of Scottih exiles and their cronies on Kersal Moor, Manchester, were the only two in England." From Sport and the Making of Modern Britain by Derek Birley.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Though it was never found out who invented golf it is generally accepted that golf goes back a minimum of 500 years. There is evidence that people started playing golf before 1457 because on 6 March, 1457 James II of Scotland banned golf and football as these sports were hampering archery practice. History of Golf brings you the interesting details about how golf gradually evolved from the medieval to the modern times. There is a legend that shepherds, while getting bored tending their flocks, used to hit stones into rabbit holes with their wooden crooks near St Andrews. They became adept at this and it led to the birth of golf on the greens of Scotland . Other Theories Some historians have also traced the History of Golf to a Roman game called paganica . They played it on the streets of Great Britain , where they ruled from 40 to 400 AD, with a bent stick and a leather ball stuffed with feathers. Others believe that golf originated from het kolven, a Dutch game. Historians even think that golf originated from a French and Belgian game called chole , a French game called jeu de mail , and an English game called cambuca . But it is generally agreed that golf originated in Scotland . Earliest Clubs Established in 1744, the Honourable Company of Edinburgh Golfers in Edinburgh, Scotland , is often recognized as the first organized golf club. The rules of the game were first written by them to settle disputes among the golfers. The Royal and Ancient Golf Club of St Andrews was founded in 1754 as the Society of St Andrews Golfers. It was they who set the standard norm of 18 holes per round. The Royal Blackheath Golf Club of England was the one of the first golf clubs to be formed outside Scotland . It came into existence in 1766, followed by the Old Manchester Golf Club founded on the Kersal Moor in 1818. It was in Canada that golf first established firm roots in North America .

It wasn't until 1888 that golf resurfaced in the United States . A Scotsman, John Reid, first built a three hole course in Yonkers, New York near his home and later that same year formed the St. Andrews Club of Yonkers on a nearby 30 acre site. From those austere beginnings, golf literally soared as a new national pastime in the United States . The popularity of golf spread from Scotland and England to parts of the British Commonwealth. The first golf club established outside Britain was the Royal Calcutta in India in 1829. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

On Politicians and Flat Building The Labour Party and the Politics of Housing in Manchester and Salford 1945-1987 Steve Fielding and Duncan Tanner are well-known historians of the Labour party. They have written sharply revisionist accounts of the party's early history and its wartime role, and are currently extending this approach through books on the inter-war years and on the 1950s and 1960s. Their role in this project extends from a broader concern with the way that Labour governed cities across the UK. Peter Shapely is a historian of urban politics, and especially of Manchester. His contribution to this pilot projects is to explore the nature and weaknesses of housing policy. Andrew Walling completed his Bangor PhD thesis on Labour politics 1951-64 in 2001. This included a case study of Salford Labour politics. The Labour councils that dominated post-war local government in many British cities built large council estates and innumerable high-rise developments. Housing programmes introduced with idealistic intentions - such as those shown in the illustrations - degenerated over time into huge failures. Many cities remain scarred by the legacy of post-war housing policy. By the time the Conservative party cut off the central government funds necessary to tackle such problems in the 1980s, the housing crisis was already a striking symbol of the broader ideological and political problems facing both the Welfare State and the Labour party. This case study of housing policy in two adjacent but different Labour-dominated cities is designed to cast light on one of democratic socialism's major post-war policy problems. Manchester and Salford were adjacent, connected, but very different cities. Manchester was a city with a mixed population, fed by suburban commuters. Salford was a densely populated, largely industrial borough bisected by road and rail networks and unable to house all its inhabitants inside its boundaries. Both councils developed interventionist housing policies. Both had left-wing Labour parties. However, there were substantial differences in the way that the parties and the Labour groups on the council operated. By the 1990s this had become more pronounced, with Manchester's council operating pro-actively to improve housing and attract new attention and amenities to the city. It became a 'model' New Labour council. Salford has not prospered in the same way, despite active efforts to devise new community initiatives. This project explores and explains these developments. It will test a series of commonly-held assumptions: that local councils made poor decisions in order to satisfy growing demand; that councils dominated by a single party were ruled by ideological - and sometimes corrupt - cliques; that local councillors were passive administrators. Many people have a very negative image of local government, Labour councils, 'old Labour' and of the period when public housing became a feature of local government activity. We will be examining whether this image is justified. Our work to date suggests we will be offering a controversial analysis. There is every indication that the idealistic post-war plans evident in other parts of the country were equally evident in Manchester and Salford and that this enthusiasm and idealism persisted into the 1960s. We have already found that in many Manchester and Salford wards, few Labour members took an active part in politics by the 1960s, and power came to rest in the hands of a few individuals. In Salford's Trinity Ward, for example, only six members attended more than half the meetings in the early 1960s. In Manchester's Newton Heath ward, most meetings contained just 10-20 per cent of the membership. We are exploring whether this was the case elsewhere. However, we have also found evidence of attempts to address this position, gain more members and involve the community. Whilst corruption existed in Salford it was matched by less-known instances of devotion and commitment to tackling a huge and seemingly intractable problem. There is some indication that 'old labour' councils of the 1950s and 1960s were rather better than the mythology would suggest, and perhaps that their failure was not just adherence to 'traditional' Labour values but a subservient support for 'modernising' ideas which in retrospect did not suit the local communities. However, we also know there was a rising tide of complaints by the later 1960s. How - and whether - the Labour party responded to this is a focus of our research. We cannot state how 'typical' these circumstances were at this stage. However, we know that domination by a small (but locally-respected) group of councillors and officials was not unique to Manchester and Salford that the decline of local Labour activism was common elsewhere and that other inner-city Labour councils faced similar problems - in some instances less energetically. However, we need to know far more about how and why decisions were made by the Labour party. Although studies of housing developments have focused on why high-rise flats were built, we also need to know how council leaders decided where that housing was to be located and who was to be rehoused. The findings from this project will be reported in journal articles, and will be summarised on these web pages. Research projects such as these are utilised in the teaching process at Bangor. They supply material for Shapely's module on urban politics in Britain and the USA and Tanner's module on the history of the Labour party. We also use these projects to provide ideas for third year undergraduate research projects.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

A History of Kersal Dale A History of Kersal Dale complied by members of the Friends of Kersal Dale.The earliest map found, a composite dated 1755-1840, shows Kersal Dale as a series of fields: Work Field at the Great Clowes Street gateway; Round Meadow at the Radford Street entrance; and Great Meadow at South Radford Street. As industrialisation brought rapid growth to both Manchester and Salford in the nineteenth century, the Clowes family decided to develop their land in Broughton, but only for grand houses and suitable public buildings, such as St. John’s Church. Kersal Dale was developed, in part for golf and in part for homes for the wealthy. Elsewhere along the Irwell, people lived and worked in squalor. For example, nearby, at Douglas Green Weir, was Douglas Mills, founded in the late eighteenth century and nicknamed ‘The Cripple Factory’, where children obtained from London workhouses were over-worked in horrible conditions. The first development on the site was the founding of Manchester Golf Course (sometimes called the ‘Kersal Links’) in 1818. The Golf Course was the oldest club between the Thames and the Tweed. The Course ceased to exist in 1960. In 1847, Manchester Racecourse opened in the River Irwell’s meander, on the opposite bank to the Golf Course. (The original racecourse was established in the seventeenth century on Kersal Moor.) In 1867, the course moved to Weaste because the land had been acquired by the Fitzgeralds of Castle Irwell. Edward was the English translator of Omar Khayyam’s Ruba’iyat. His less famous, but more eccentric, brother, John, disapproved of horse racing. On Fitzgerald’s death in 1898, the land was bought back by the Racecourse Company and, in 1902, racing returned to the site. The course was extended and stables were built opposite the Cliff, on Kersal Bend. Castle Irwell, built in 1826, was demolished, as was most of the wooded knoll which it occupied. The shadow of that knoll can still be seen by looking across the river from the end of Hugh Oldham Drive. East of the Golf Course, on the land bordering Bury New Road, an 1848 map shows us three houses - Kersal Lodge, Walker’s Croft and Kersal House - in landscaped gardens with pools, fountains and statues. By 1851, Sycamore Cottage had been built, (just at the foot of the steps down from the Great Clowes Street entrance). Kersal Dale Villa first appears on an 1888 map, built behind Walker’s Croft, which was, by then, called Willow House, possibly because it had been either extended or re-constructed as a larger house. For fifty years or so, Kersal Dale, and the surrounding area, was elegant, opulent and bucolic. The Victorian painting of the area depicts the River Irwell at Kersal Dale as a place of recreation. Writing in 1907, Salford’s Borough Engineer describes the beginning of the decline of Kersal Dale as a cultivated area: Here we enter the still beautiful bend of the river below The Cliff, Kersal Dale and Kersal House. Many extensive and flourishing gardens still remain on the hillside around this bend, though the smoke of the town has destroyed some of their former luxuriance. There are still many fine trees, and owing to its quietness many species of wild birds still frequent the place, and there are also flying visits from the more migratory species, so that, I am sorry to record, sundry “sportsmen” go shooting in this neighbourhood. J. Corbett, The River Irwell, Abel Heywood and Son, Manchester, 1907, p.67 As Bracegirdle notes, “In the early decades of the nineteenth century the owners of the new industries often built their homes along pleasant stretches of the Irwell…but increasing pollution from their own factories gradually forced them to retreat to outlying villages”. C. Bracegirdle, The Dark River, John Sherratt and Son Ltd, Altrincham, 1973, p.125 A 1922 map shows all five grand houses still existent, (whether occupied or not), but a 1954 map shows all but Kersal House as ruins. In February 1882, there was a large landslip at Great Clowes Street and Bury New Road. Further slips occurred in 1887 and 1888 and again in the early 1920s, leading to Great Clowes Street being closed to ‘mechanically propelled vehicles’ in 1926. Many schemes for addressing the problem were considered and attempted, beginning in 1882 and ending, after further landslips in the 1940s. The first scheme undertaken in 1882 revolved around drainage of the Cliff. A retaining wall at Great Clowes Street and further drainage were considered but not attempted in 1887. In 1901 and 1907, it was proposed that a river wall was built. In 1925, a concrete and brick retaining wall was built to address a local slip behind Sycamore Cottage. On 15 July 1927, the worst landslip happened, causing part of Great Clowes Street to fall away. It is this event which seems to have been the cause of the abandonment of Sycamore Cottage, Kersal Lodge, Willow House and Kersal Dale Villa. While all are listed, together with occupants, in the 1927 directory, they are absent from the directory for 1928.

For an account and pictures of volunteers working on Kersal Dale click here |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

On Salford Flats Causing Rain in Manchester Manchester rain blamed on Salford high-rise flatsGuardian, 13th September 2002 Mancunians who bemoan their city's sogginess have been offered an unexpected scapegoat - the tower blocks down the road. The persistent drizzle is largely due to the multitude of high-rise blocks built in the neighbouring city of Salford during the 1970s, it was claimed yesterday. According to Christopher Collier, a professor of environmental studies at Salford University who formerly worked for the Met Office, buildings can have as much impact on local weather as global warming; an urban development can make areas wetter or drier depending on how it affects temperature and air currents. Plans to double housing density in the south-east were likely to have a dramatic influence on the region's weather patterns, he claimed. Prof Collier has studied the climate effects of development in Greater Manchester. He found that the high-rise flats and offices which sprang up during the 1970s had led directly to an increase in annual rainfall levels of 50 millimetres south-west and downwind of Salford. North and north-east of Salford, heavy rain had become less frequent but persistent drizzle more common. Part of the reason was turbulence caused by air passing over the jagged tops of tall buildings. The "roughness" threw up low-level air allowing it to cool, so that water vapour condensed into rain. At the same time dust particles caused by city pollution led to smaller than normal raindrops forming in clouds. This helped explain Manchester's famous drizzly sogginess. "Manchester has a reputation for drizzle and miserable weather, and it might have something to do with that mechanism," Prof Collier told the British Association festival of science. He added that there was an 8C temperature difference between Salford city centre and the surrounding countryside. "This also has led to changes in circulation which have reinforced the changes in roughness," he said. Government plans to increase housing density in the south-east from 24 dwellings per hectare to 30-50 per hectare would have unpredictable effects, Prof Collier warned, harmful in some areas and beneficial in others. "These changes may have a magnitude comparable or certainly approaching those due to climate change. "Town planners should be aware of the impact of their buildings on weather." |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

On The Closing Of Kersal Way To The Public

SALFORD CITY COUNCIL

PURPOSE OF REPORT. This report details the proposed introduction of a permanent Prohibition of Driving Traffic Regulation Order on Kersal Way in Kersal Ward, Salford and thereby extend and replace the existing lapsed temporary order . RECOMMENDATION. That approval be given to the recommendation to introduce a permanent prohibition of driving order on Kersal Way as indicated in the report. ROUTE Regulatory Panel (Planning and Transportation) IMPLICATIONS.

WARD(S) AFFECTED: KERSAL WARD COUNCILLORS: P.CONNOR, D. A. MILLER, G.W.WILSON SERVICE DELIVERY AREA: KERSAL CONTACT OFFICER: M.W.KEAN (X3842)

a) KERSAL WAY, SALFORDAs part of the proposed redevelopment of land adjacent Kersal Way, which connects South Radford Street and Kingsley Avenue in Kersal, Salford, a temporary prohibition of driving order has been in operation since 12th May 1997. It was always intended that the temporary order, which was for an initial period of 18 months, would be sufficient for the developers of the land, Regalian Homes Estates Limited, to complete the phased construction of the development and reopen the highway to public use. The prohibition of driving was introduced to enable the reconstruction of the highway and to prevent its deterioration due to fly tipping and to prevent the highway being used for the abandonment of stolen vehicles and other anti-social behaviour. The temporary order made in 1997 lapsed in 1998 but another was introduced in October 1999 for the maximum period allowable to November 2001. Regalian the developers are due to surrender part of the development agreement with the council due to market conditions and only develop a proportion of the original site. However, it is considered that the highway should still be closed to general traffic and as another temporary order is not strictly the correct legal process to follow to enforce such a closure, it is proposed that a permanent prohibition of driving order is introduced until such time as the redevelopment of the area takes place. Local representatives have requested that the length of the closure is extended so that it will commence at the junction with Kingsley Avenue and not some 35 metres north of it as at present. The Greater Manchester Police and local ward councillors are in agreement with this proposal. The large boulders, which enforce the prohibition of driving, will be relocated nearer to the junction with Kingsley Avenue.

RECOMMENDATION Introduction of a Prohibition of Driving Order on Kersal Way, Salford, from its junction with Kingsley Avenue to a point 185 metres south east of South Radford Street

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

On Redevelopment

New Deal For Communities New Deal for Communities (often referred to as NDC) is part of the government’s strategy to improve the most deprived neighbourhoods in the country. This multi- million pound project aims to make Charlestown and Lower Kersal a place where people want to live. One of the most important parts of the area’s transformation will be the building of new homes, including the Charlestown Riverside and Lower Kersal Riverside areas, and the former Kersal High site. The new development will provide a number of affordable new homes for local people, as well as aiming to attract new people to this part of Salford. In all, 351 existing properties in Charlestown and Lower Kersal are affected by the plans to transform the area. We are keen to retain the local people who want to stay in the area, and our teams continue to work with and support local residents throughout the development. What has happened so far 2003

2005

You will get priority on the council’s

housing list.

You will get appropriate housing priority to help you

find alternative accommodation. However, this priority

will not be awarded until the council determines

From the Charlestown and Lower Kersal NDC "Redevelopment Information Pack 2." November 2006

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Spot The Grot, Stop The Rot This is a report that was designed to spot urban decay early and deal with the problem before it became widespread in an area, and hence socially damaging and extremely expensive to fix. Thus Lower Kersal and other areas were analysed in terms of house prices, community participation etc. This report was compiled by David Blackman for the Royal Institute of Chartered Surveyors in 2005. Click Here

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

From "Biodiversity By Design - A Guide For Sustainable Communities" produced by Town and Country Planning Association in September 2004.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

On Kersal and Salford As The New Hollywood You may be interested to know that there is an organisation called REELmcr. "I think I should say that REELmcr is not a film production company but rather a community centered organisation that uses the processes of drama, writing and film making to encourage participants to explore the issues that affect them and their communities. The REELmcr process is designed to challenge a narrow view of life and present the possibility of new friendships, alliances and opportunities for change. " Terry Egan (director REELmcr) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

FAMELESS

FAMELESS AT THE LOWRY

From http://salfordstar.blogspot.com/

See also the Salford Film Festival

|

Fameless, a local film by local people29/ 6/2005 JACQUI Carroll, the director of REELMcr’s latest community film, laughs nearly all the way through our conversation. She’s frantically putting the finishing post-production touches to Fameless; a comedy that promises, ‘profundity, fun and a massive roar back at those who stereotype Salford’. The film was shot in four days and edited in three and while the editor is at home getting a well needed kip, Jacqui’s up and about and chuckling with excitement at what’s been achieved so far and the prospect of a well received premiere at the Lowry on July 2nd. The media hysteria surrounding the supposed ‘ASBO culture’ of working class communities motivates the films being made by REELMcr. In Fameless it’s the turn of Charlestown, Pendleton and Lower Kersal people to cut through the two-dimensional perception of them peddled by certain ‘culturally elite’ sections of British society. The script, devised around the theme of tolerance and written in collaboration between mums, dads and kids from the area and Salford-born playwright Christopher Green, actively subverts preconceived notions.Turning the tables, it focuses on a film-crew that gatecrashes Salford looking to cash in on the reality-TV gravy train and get some titillating footage of the disenfranchised, only to get more than they bargained for: |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||